Deepseek mHC: How a 1967 Algorithm Fixed a 2025 AI Problem

For all its complexity, the current AI era runs on a relatively simple formula:

Take the standard Transformer architecture and scale it until something breaks.

Throw the proverbial computing kitchen sink until something works (or ‘cooks’, according to kids these days).

But on January 2nd, while most of us were wrapping up New Year’s celebrations, DeepSeek published a paper that solves a specific scaling problem using an algorithm from 1967…back when computers filled entire rooms and ran on punch cards.

It’s called Manifold-Constrained Hyper-Connections (mHC) and in this article I explore what it is, why it matters, and what it means for safety & governance.

Neural Networks and Depth

Neural networks are stacked layers. Layer 1 transforms data, passes it to layer 2, which transforms and passes to layer 3, and so on. More layers = more complex patterns the network can learn.

Straightforward enough.

The problem showed up when people started stacking dozens upon dozens layers which led to gradients exploding (numbers reaching 10^16) or vanishing (shrinking to zero).

Either way, the training stopped working.

ResNet Fixed It

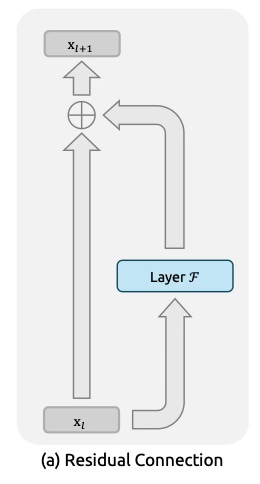

Then in 2015, ResNet solved this problem with residual connections.

It’s a simple but brilliant idea.

Just pass the input forward unchanged while letting each layer add a small adjustment.

It’s like the old telephone game but now players also pass a written note forward while whispering additions to the next player. Whispers may get corrupted but the note stays readable.

Mathematically:

Output = Input + Layer(Input)

And voila!

That identity mapping (passing input unchanged) keeps gradients flowing cleanly during training. The network doesn't rely on every layer being perfect; even if a layer learns nothing, the data still gets through.

This became the foundation of modern deep learning.

The seminal 2017 Transformer paper ‘Attention Is All You Need‘ uses it. GPT uses it. Gemini uses it.

Every major language model now relies on residual connections.

Hyper-Connections: Widening the Highway

ResNet’s single residual stream works, but it creates a bottleneck. As models scale to billions of parameters, that single lane limits capacity.

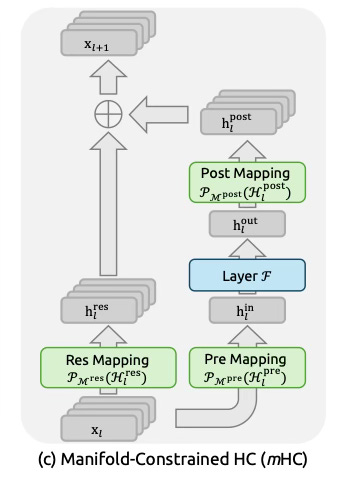

Hyper-Connections (HC), published in 2024 by ByteDance, expanded this one lane to multiple parallel lanes. Instead of one residual path, HC uses four streams that exchange information via learned mixing matrices.

Mathematically:

Output_streams = Input_streams + Mixing_Matrix × Layer(Input_streams)

Each stream carries different features. The mixing matrix controls how information redistributes between them. More lanes, smarter merging, richer representations.

On smaller models, this worked as the performance improved and features became less redundant.

YAY!

Then DeepSeek scaled it to 27B parameters.

The Crash

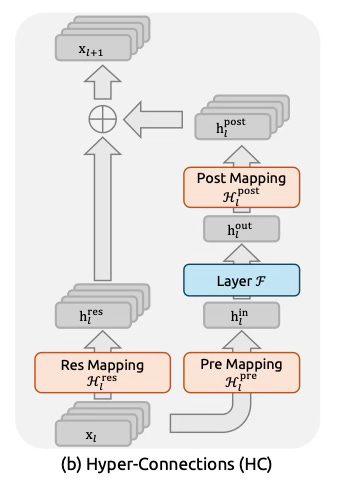

The 27B model broke because of unconstrained signal amplification.

The mixing matrices in HC are learned parameters with no restrictions. When you compose these matrices across 40+ layers, small amplifications compound exponentially. A 1.2x amplification per layer becomes 127x over 20 layers and 14,000x over 40 layers.

DeepSeek measured composite signal gains reaching 3000x. In some simulations, gains hit ~10^4 around depth 50+.

OOF!

Think of it like audio Feedback in mic.

If you put a microphone too close to a speaker, the signal loops and amplifies until you get that ear-piercing screech. Unconstrained mixing matrices do the same thing to neural network signals. They amplify noise 3000x in both forward and backward passes.

No gradient clipping will help at 10^4 as you’re fighting the architecture itself.

At that point you’re not training a model.

You’re heating the datacenter.

Manifold-Constrained Hyper-Connections

In 1967, while the Beatles were releasing Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, two mathematicians were publishing a paper on iterative matrix normalization.

One of those releases would solve DeepSeek's 2025 gradient explosion problem. (Hint: it’s not The Beatles.)

DeepSeek’s solution for HC: to fix the explosion, they need not change the structure of the highway (the multiple streams). They just needed to enforce a strict speed limit on the traffic.

Mathematically, they determined that the mixing matrices couldn't just be random learned numbers. To guarantee stability, they had to be Doubly Stochastic.

In plain english:

All entries positive

Each row sums to exactly 1.0

Each column sums to exactly 1.0

To enforce this, they used the Sinkhorn-Knopp algorithm.(1967) which takes any learned matrix and iteratively projects it onto the "Birkhoff polytope" which is a geometric space where all dimensions are perfectly balanced.

Here is a simple illustration:

Hyper-Connections matrix:

To→ S1 S2 S3 S4 Row sum From↓ S1: [0.6, 0.2, 0.1, 0.5] = 1.4 S2: [0.3, 0.9, 0.2, 0.1] = 1.5 S3: [0.5, 0.1, 0.8, 0.2] = 1.6 S4: [0.2, 0.4, 0.3, 0.7] = 1.6 ─────────────────────── Col sum: 1.6 1.6 1.4 1.5 ✗

Notice the rows and column sum to more than 1.0?

Stream 1 for example is amplifying by 40%. Do this across 60 layers and you’re multiplying: 1.4 × 1.5 × 1.6 × ... 60 times

DeepSeek forces every matrix to be doubly stochastic:

mHC matrix:

To→ S1 S2 S3 S4 Row sum From↓ S1: [0.4, 0.2, 0.3, 0.1] = 1.0 S2: [0.3, 0.3, 0.2, 0.2] = 1.0 S3: [0.2, 0.3, 0.3, 0.2] = 1.0 S4: [0.1, 0.2, 0.2, 0.5] = 1.0 ─────────────────────── Col sum: 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 ✓

Now, thats better.

DeepSeek applies this projection after every parameter update. The model learns mixing matrices freely and then projects them using Sinkhorn-Knopp before the forward pass.

Deepseek believed this will get you the capacity of multiple streams without sacrificing stability.

The Results

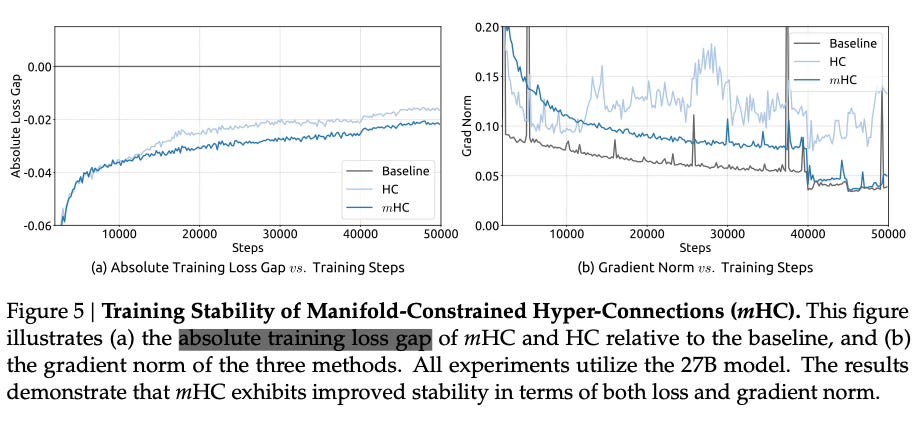

So were they right? Is mHC actually more stable?

The answer is yes. Very much so.

The 27B HC model showed loss surges and gradient explosions at 12,000 steps. mHC trained smoothly with no instability.

The composite signal gain stayed bounded near 1.6x, whereas the previous HC model hits 3,000x.

The final training loss was also 0.021 lower than the baseline.

So it is stable...good…but is it smarter? I hear you ask.

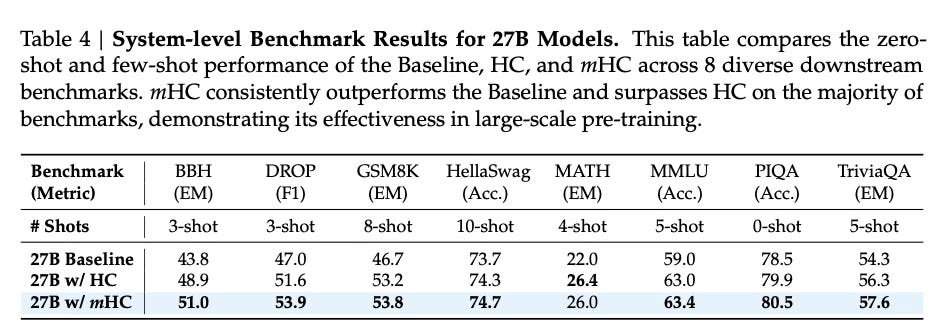

The answer again is yes. It improved on downstream benchmarks over HC.

BIG-Bench Hard (Reasoning): +7.2 points (51.0% vs 43.8% baseline).

DROP (Reading Comp): +6.9 points (53.9% vs 47.0% baseline).

GSM8K (Math): +2.8 points (84.9% vs 82.1% baseline).

Maybe the training overhead is higher…right?

Yes but it only shot up 6.7%. In exchange, you get 4 parallel streams that stay stable at scale instead of exploding.

A worthwhile trade for the stability and performance gains you get in return.

Let’s give it a spin?

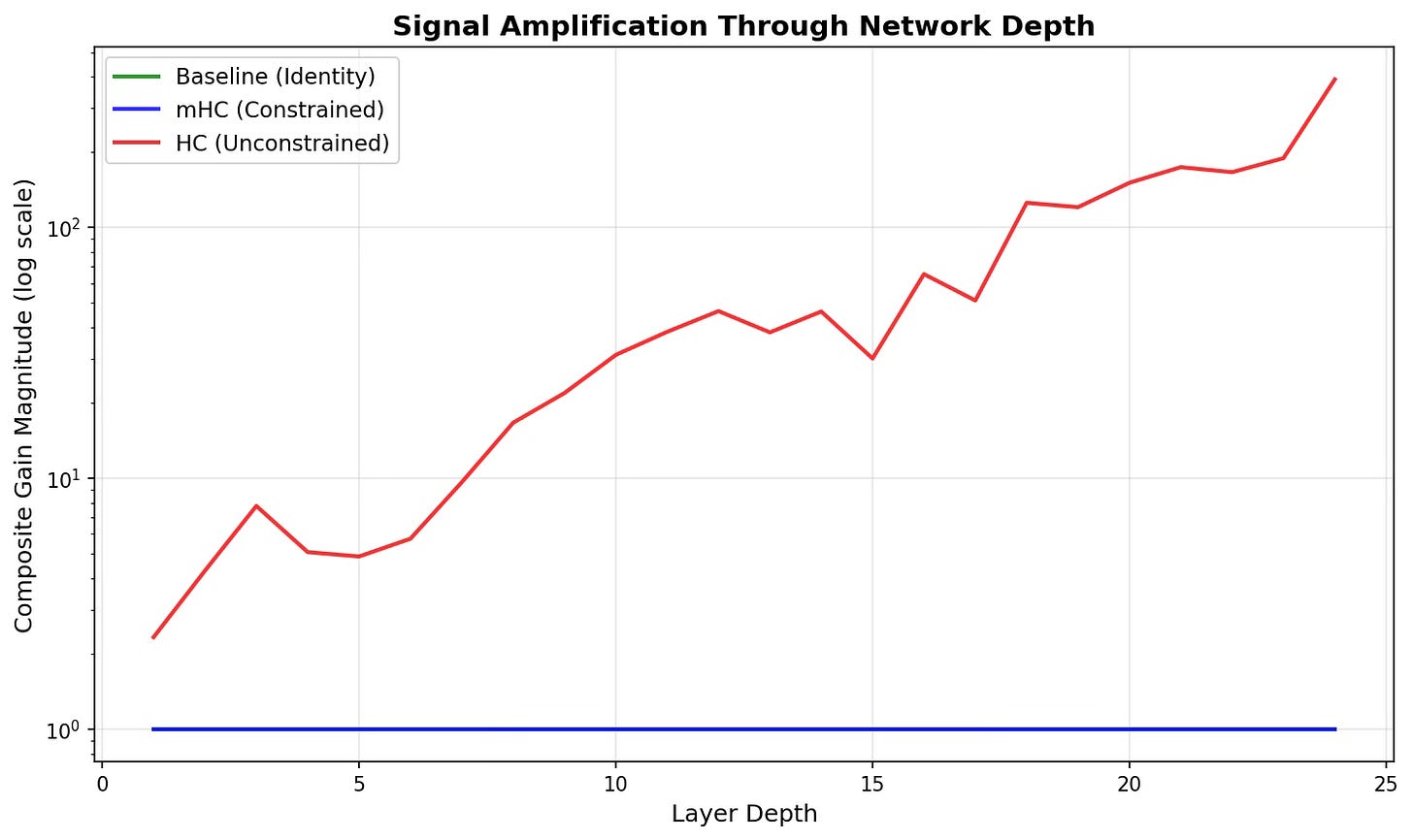

I simulated the mHC at a toy scale to confirm if the math is indeed math-ing.

Full code available in this Colab notebook if you want to run it yourself.

I used 4 streams, and 24 layers with random initialization. I then measured composite gain (signal amplification through depth) and gradient norm (training stability over 500 steps).

This is how the gain amplified:

The invisible green line (Baseline) stays flat at 1.0. Standard ResNet as expected.

The red line (HC) explodes exponentially right from the get go. By layer 24, composite gain is mimicking S&P 500 post 2021.

Unconstrained matrix adding multiplicative factor = Explosion.

Our protagonist , the blue line (mHC) stays flat at 1.0.

The Sinkhorn-Knopp projection is working. Even with 4 parallel streams and learned mixing, the doubly stochastic constraint prevents signal amplification.

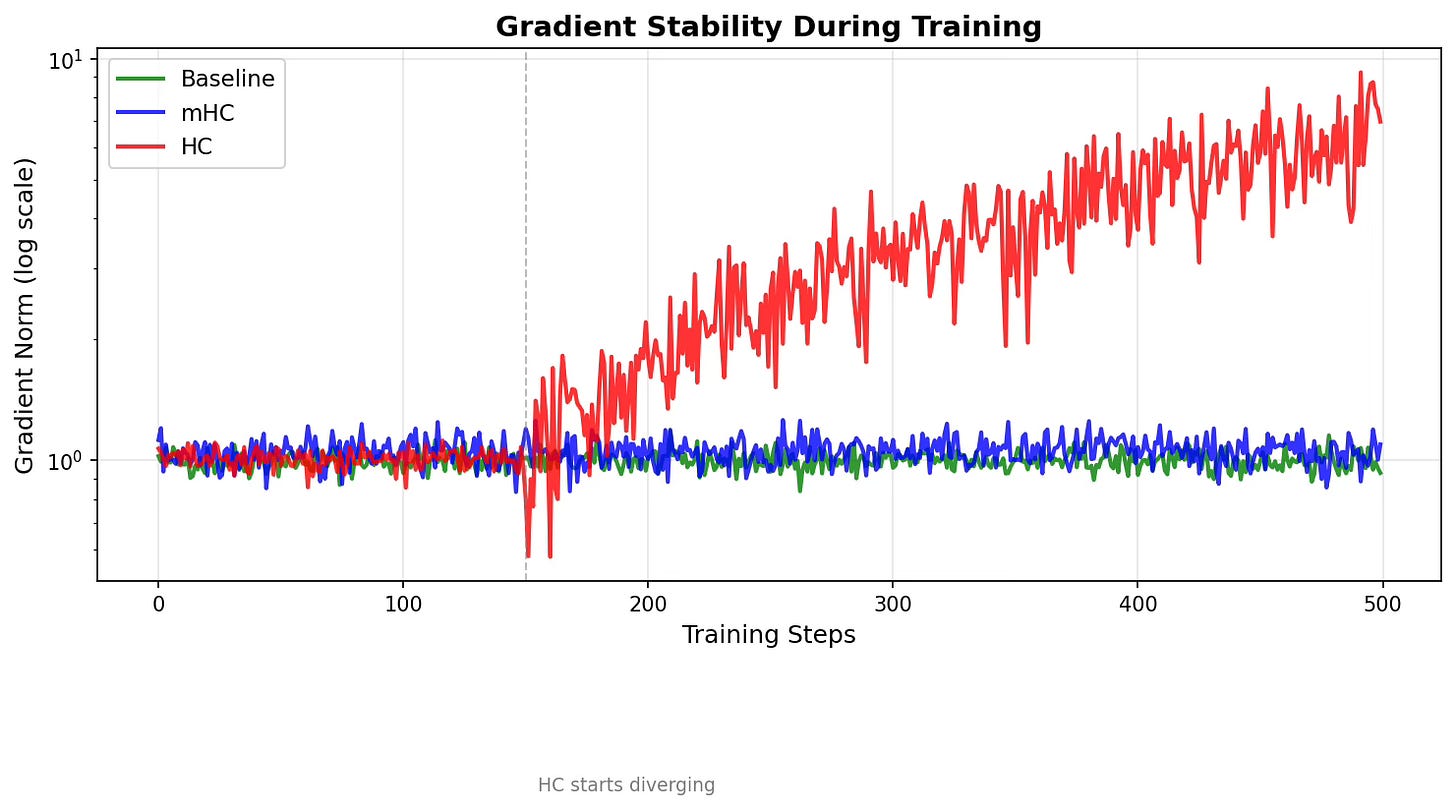

Now looking at the Gradient Norm (Stability):

For the first 150 steps, all three lines track together. Green (Baseline), blue (mHC), red (HC) are indistinguishable.

Around step 150, HC starts diverging (marked with the gray dotted line). This confirms the paper i.e the training proceeds normally, then suddenly becomes unstable.

By step 300, HC is clearly climbing while baseline and mHC stay bounded.

By step 500, HC gradient norms are ~7x higher than baseline.

Damn!

Once again our hero, mHC is cruising smoothly with the baseline.

This was the final measurement at step 500: Baseline 0.93, mHC 1.10, HC 6.97

Yes, this is toy scale (thousands of parameters, not billions) and yes, I didn’t test the full transformer architecture, real language tasks, memory optimizations, scaling beyond 24 layers, or downstream benchmarks.

But the core premise of the paper holds up well in our toy simulation. HC’s Unconstrained mixing matrices amplify signals exponentially. mHC’s doubly stochastic constraint prevents it from exploding.

THE MATH IS INDEED, MATHING!

What This Means

mHC shows architectural design still a critical variable. Most attention goes to scaling laws and datasets, but how layers connect affects both performance and stability.

It is telling (and cool) that they used a 58-year-old algorithm to fix such a modern problem. This serves as a reminder that we haven’t exhausted classical mathematics for machine learning design, even in the current era of benchmark hype.

Will the industry adopt it?

Maybe.

Most engineering teams have already optimized for standard transformers. Switching requires re-engineering and faces adoption inertia.

But the 6.7% training overhead is small, the gains are real, and the paper is public. The technical work is solid enough that it deserves serious attention.

One can safely assume DeepSeek applies this in their much anticipated V4 model. Their V3 model competed on cost, and now mHC proves they have solved stability at scale.

V4 isn’t just cheaper, it will be deeper and more complex.

I will be looking forward to that release.

Governance & Safety Gap

We may not think it but training stability matters for safety.

When a 27B model crashes at step 12,000, you can’t evaluate intermediate checkpoints or measure how capabilities emerge. mHC makes training more predictable, which helps evaluation.

But here’s the gap:

DeepSeek published loss curves and benchmarks. They didn’t publish systematic evaluation of how mHC affects emergent behaviors or safety-relevant capabilities.

Does multi-stream information flow change deception propensity? Situational awareness?

We don’t know.

This pattern repeats itself regularly. The race to produce architectural advances, measure its performance and quickly ships models is faster than the race for safety.

And, safety evaluation lags because we lack frameworks for assessing architectural changes.

The frameworks evaluate models, not architectures. mHC is an architecture change. Does it make models safer, riskier, or neither? We don’t know because we haven’t built the evaluation infrastructure.

Training stability is directionally good as predictable behavior beats uncertainty over time. But stability isn’t proportional to safety. A model can train smoothly and still exhibit harmful capabilities.

The governance & risk community needs frameworks that can assess architectural changes specifically rather than just waiting to test the final output. Innovation is moving faster than our ability to measure its implications.

And that is worth thinking about while amidst the benchmark hype.